The other day Tristan, my oldest (6-year-old) son, asked an excellent question.

“Dad, is Earth 2,025 years old?”

Kids have an innate gift for asking such seemingly simple yet profoundly difficult questions. Ones we adults don’t even think to ask and are often challenged to answer.

His intuition is natural. Why wouldn’t it be 2,025 years old? All of our calendars say as much.

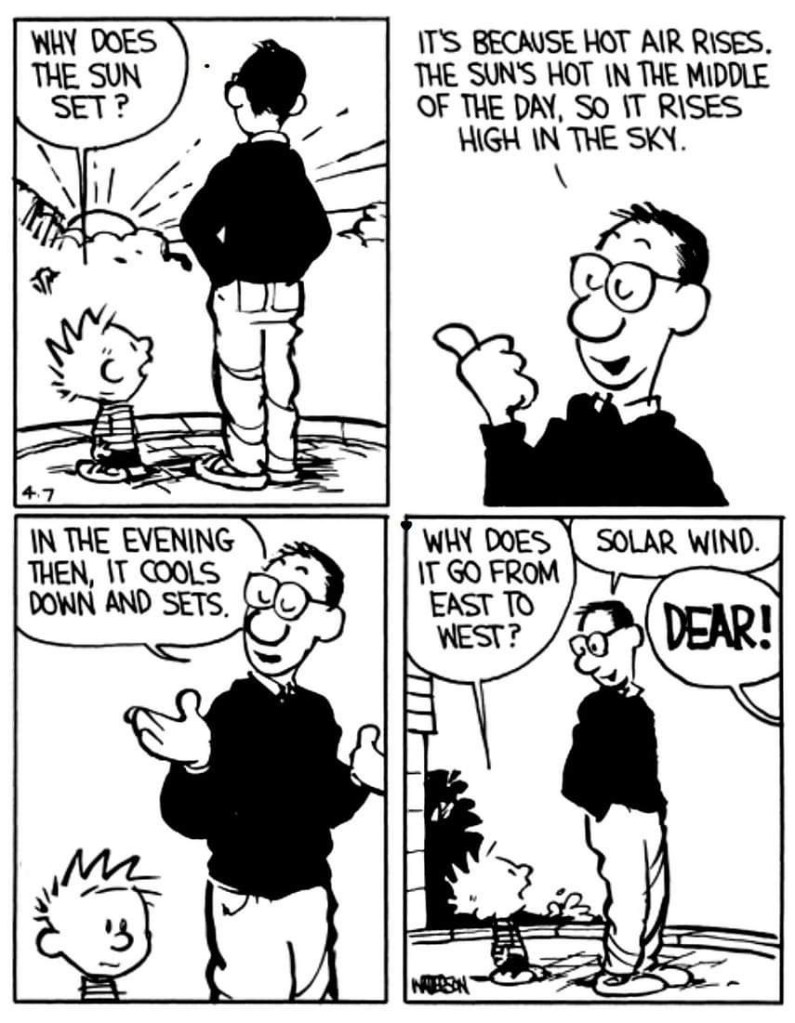

Put on the spot, I don’t think I did a great job articulating my response. I obviously answered no, but the very apparent follow up questions were difficult to address. If you asked Tristan, he would likely say he had no idea what I was trying to say. It probably resembled something similar to this conversation between Calvin and his father…

Many Christians, like myself, will continue to wrestle through this dichotomy that has been handed to us. First, that the scientific consensus largely holds the belief in a very old Earth – billions of years old. And second, that if one were to take a very strict literal interpretation of the Bible, that Adam and Eve (and therefore we assume Earth) were created roughly 6,000 years ago.

This topic ignited theological, political, and cultural arguments in the early 20th century, due to the growing adoption of this new evolutionary theory, and the associated old Earth cosmology. It might seem trivial but, at its core, that fight was over whether the world was crafted with intentionality or simply the result of natural selection and randomness. Was the creative process top down or bottom up? Was there meaning and purpose to existence or not?

Those discussions have slowly faded over the past several generations. I suspect many in the church have gone quiet on this issue to avoid the discomfort, opting to ignore the topic instead of fiercely debating it.

And while ignoring this uncomfortable topic is certainly a strategy, I don’t think it’s the best one. I don’t know if my kids will let me plead ignorance. And for my own sake, I want to give this some thought.

If the assumption is that God created everything from nothing within literal days prior to his creation of Adam and Eve, these conflicting understandings of the age of our planet would seem to be irreconcilable. Hence the fierce debate.

And this has often led to two oppositional approaches for those who choose not to simply avoid altogether. You can dismiss or selectively choose scientific findings to uphold this particular form of literal reading of Genesis. Or you can diminish or discard the Bible, or at the very least the Old Testament, for the sake of adopting the currently prevailing scientific view.

But is it possible that there is a third way of approaching this question?

Both kids and adults alike are fascinated and unsettled by this question. I’m no exception. I want to try to understand it well enough to translate to my son another potential viewpoint. One that allows us to engage with both worldviews because I don’t think they need to be considered mutually exclusive. Is it possible to hold the Bible in highest regard while also giving credence to what we believe to be valid scientific findings?

Some may accuse me of mental gymnastics on this. So be it. But I wanted to share honestly how I have tried to grapple with this question. Not that I have all the answers or that my opinions won’t change with time.

But I’m viewing this post as an attempt at describing this third way, an approach that can be described as a functional or theological reading of Genesis 1 rather than a material one. That this passage isn’t concerned with God creating matter. It’s narrating how he creates an ordered world from disorder.

Is Earth 2,025 years old?

The immediate answer to Tristan’s question is undoubtedly the easiest to answer. No, it isn’t 2,025 years old. But it’s the very obvious follow-up questions that make this challenging.

If Earth isn’t 2,025 years old, then how old is it? And why do we state the year as 2025? Why not 1? Why not 4,540,000?

Again the easiest answer to give is to say for many centuries the year 1 from which all our calendars are measured, has traditionally corresponded with Jesus’ birth. I think many people are aware of that. Whether you have faith in Jesus or not, we have been handed this method of telling time by our ancestors who did.

For me, that raised some questions of my own. When did we decide to retroactively ascribe this date though? The way we number years today can feel so natural that it’s easy to assume it has always been that way.

A little researching made me aware that the AD system was introduced in 525 AD by a Christian monk named Dionysius Exiguus. His goal was not to create a universal calendar, but simply to calculate the date of Jesus’ crucifixion. To do so, he proposed counting years forward from what he believed to be the year of Jesus’ birth, labeling it Anno Domini—“in the year of our Lord.”

This system was not immediately adopted though. For centuries, people continued to date years based on local rulers, reigns of emperors, or significant political events. It wasn’t until the 8th and 9th centuries that AD dating became common in Europe. Even then, it took many more centuries to become the global standard we use today.

Modern historians also believe Dionysius was likely off by several years in estimating Jesus’ birth, meaning our calendar is also slightly misaligned with the event it references.

In other words, the year “2025” is not a measurement of Earth’s age, nor even a precise measurement of how long it has been since Jesus was born. It is a culturally inherited reference point, chosen for religious reasons, that was slowly standardized over time.

We have always measured time, but not all cultures have measured it the same way or for the same reasons.

In the ancient world, years were often counted according to the reign of a ruler. “In the third year of King so-and-so…” “Ten years after the great flood…” “Five years after the founding of the city…”

The Jewish calendar dates years from what is traditionally understood as the creation of the world, placing the current year at roughly 5,700+ years, which is very close to the 6,000 years many modern Christians state. This number is derived from genealogies and narratives in Scripture. Interestingly, it also falls within the broad era generally associated with the rise of the earliest cities in ancient Mesopotamia.

The Islamic calendar begins in 622 AD, marking the Hijra, Muhammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina..

The traditional Chinese calendar cycles through repeating eras tied to lunar and solar patterns, emphasizing harmony, cycles, and renewal rather than a single linear starting point.

Modern science uses yet another framework entirely. Methods like radiometric dating, astronomy, and geology allow scientists to estimate the age of Earth at approximately 4.54 billion years. This number is not tied to human events at all, but to physical processes measurable in rocks, stars, and atomic decay.

Even the French Revolutionaries in the late 18th century wanted to start over from year 1 on their calendar and break from the AD system. They wanted their movement to no longer be associated with the Christian story. They wanted to write their own.

Throughout human history the reference point used for timekeeping means more than just a number. Calendars do not tell us how old the world is. They tell us what a culture considers important enough to measure time from. They tell us what story we are living within.

Timekeeping has throughout human history been functional and relational, not absolute.

Earth was Established When?

Very often you will drive by a restaurant or company that notes the date of their establishment. Sometimes it’s to indicate the amount of experience they have. For others it seems to be to indicate their newness. For others it seems just to be a sense of pride, a reminder of when or where they started.

But what do they mean by establishment?

Is it the date the building was built? Not necessarily. Some companies retrofit existing buildings and some don’t use buildings at all. Some even move to new locations or demolish and rebuild new buildings while maintaining the same establishment date.

Is it the date of birth of its founder? Is it the date a chef came up with their first recipe, the owner got their degree, or the furniture within was built? The answer to all of these are obviously “no.”

It is very clear that this establishment date marks the initiation or creation of something, not in a material sense, but in a functional sense.

The combination of employees, services, values, culture, history, and yes to some degree, the material components like buildings, furniture, and material assets, aligning together to serve a particular function.

It is this date, when doors are open to treat patrons to a new culinary experience, product or service, that marks its beginning. Where the sum has become greater than its parts. When the creative process has hit the pivotal moment where it can be shared with others.

So what is the Earth’s establishment date?

What does “Create” mean in Genesis?

The term “create” used in Genesis 1 is בָּרָא (baraʾ). The intended meaning of this word is better understood not as creating something from nothing as many posit, but as creating something functional from the disparate raw materials. This creative role is more like a CEO establishing a company or a sculptor creating a moving piece of artwork from a block of marble.

Unfortunately, by trying to find congruence between the modern materialist view of the universe’s beginnings, many Christians have flattened the text, treating it like it’s a scientific order of processes instead an ancient work of literature that is borrowing and differentiating from the polytheistic worldviews of their neighbors at the time.

Very quickly in the text one would see that God has made light before he makes the stars in the sky, which doesn’t map cleanly onto our modern understandings of how this works scientifically. If Genesis 1 were an instruction manual for making the world, it appears some steps are out of order.

But that’s not the purpose of this text. As John Walton, a biblical scholar and author of The Lost World of Genesis One observes, the seven days of creation are better understood as follows:

Days 1-3 God creates functions by dividing or separating. Day 1 establishes time by separating light from dark. Day 2 establishes weather via the separation of waters above and below. And Day 3 establishes agriculture with the separation of land from the sea.

Days 4-6 God creates functionaries by filling these spaces. Day 4 provides the stars and moon. Day 5 provides the birds of the sky and fish of the sea. Day 6 provides the animals, including man, on the land.

And Day 7, God rests. He abides in his newly made temple (Earth), essentially taking his place in the control room of his newly established corporation. Earth now serves its intended function. Order was established from chaos.

In this ancient cosmology, the world manifest itself in the cycles and patterns of life: sunrises and sunsets, seasons, and the ritualistic patterns of animal migrations and habits. And, contrary to the beliefs of their neighboring cultures, God was not the sun, moon, animals, skies or seas but transcends all of them.

The text beautifully and succinctly describes how a world with very clear structure and function was designed intentionally and not just the result of randomness, much in the same way a corporation or restaurant does not just accidentally emerge from nothing.

So How Would I Answer Now?

If given a second chance at this question, here’s how I would try to answer:

No, Tristan the world isn’t 2,025 years old. It has existed for billions of years. But God slowly formed it into the type of place where people could start building, farming, caring for animals, and being creative themselves in a similar way to how God is creative. God was taking his time to make a world where both he and us could reside.

The 2,025 years reminds us of when Jesus was born. And with each passing year when that number changes we’ll be reminded again of Jesus.

I will continue to wrestle through this and suspect I will never have a completely confident answer in this lifetime. And that’s okay. If anything I hope it leads me to more awe and humility.

I think there’s a reason this topic has historically been absent from the church’s creeds. It’s important but not the most central aspect of the Christian faith. And I think there’s room within the Church for some varying interpretations.

But I’m glad that I have a son who will challenge me to think deeply about this and maybe find more appreciation for the seemingly mundane parts of life I’ve taken for granted. Something even as simple as the year on the calendar.

For it reminds us of what our culture has historically recognized as most foundational. The life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It’s a story we can live in too and be reminded of with each passing year.

That is, of course, if we see it as more than just a number.