“Hey Dad! Hey Dad! 6 7!”

Accompanied by a juggling hand motion, Tristan was showing off the new meme he had learned at school.

For those adults who are completely unaware of what I’m referring to, kids just say the numbers “6 7” and typically laugh to themselves.

This phrase has gone viral among kids largely because it baffles the adults around them. “What does it mean?” “Is it something inappropriate?” “Why do they think this is so funny?” “It doesn’t make any sense!”

Fortunately, coworkers had forewarned me of this new fad that their older kids had been doing. We all knew it wasn’t anything nefarious. My coworkers were just perplexed by it.

What apparently started from a rap song and became widespread via an NBA player on social media had now spread far and wide. And I naively thought it would stay to the older grades.

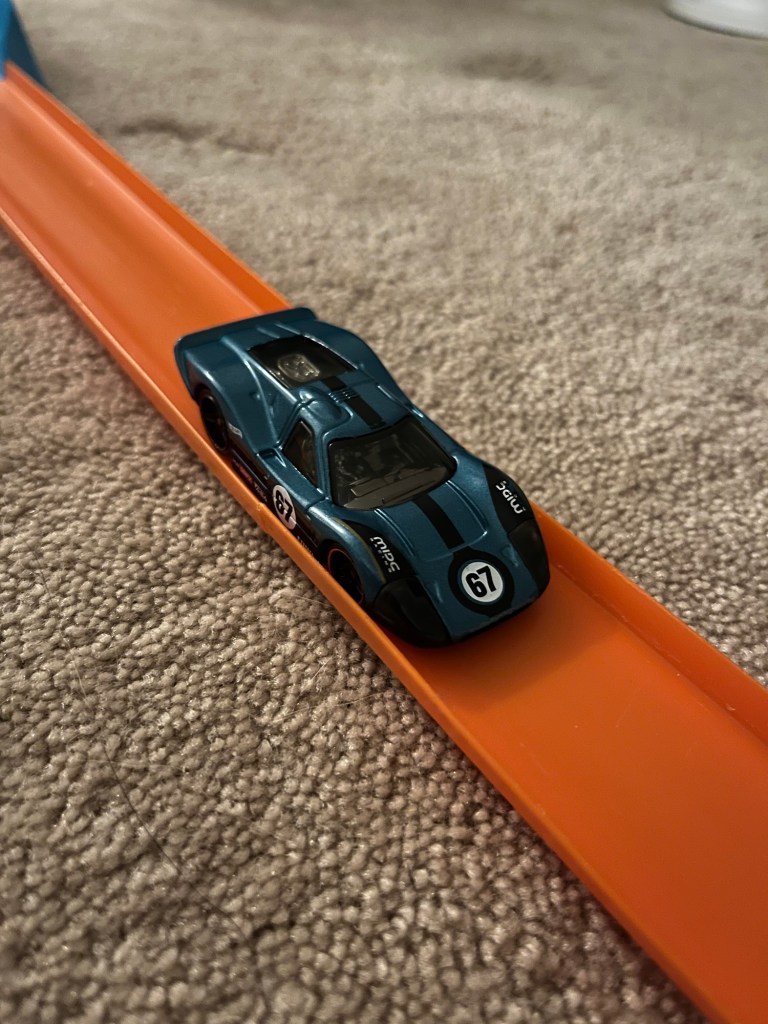

Our son was recently gifted a car with the number 67 on it. Immediately Tristan remarks, “Dad, look it’s 6-7!”

The temperature hits 67 degrees on the thermostat. He collects 67 rings in his new Sonic game. Football score pops up and in all cases… you guessed it… “6 7.”

Does Tristan know the origin of this? Not at all. And the same can be said for probably 90% of the kids playing around with this. For them it’s the intrigue of it. It’s playful. It’s an inside joke. It’s nonsensical. And the frustration it causes for some parents and other adults in their lives is what makes it that much more appealing to them.

It got me thinking though how coincidental it is that the two numbers in this little joke happen to be two of the most interesting, and in some ways intriguing, numbers in the Bible. 6 and 7.

The Biblical Meanings of Numbers

There are many numbers in the Bible that seem to communicate more than just their numerical value. 3, 12, and 40 are a few of them.

3, a number of divinity or completion. Jesus rose on the third day. Jonah was in the belly of the fish for three days. The Trinity – Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Even the repetition of a word three times in ancient Hebrew and Greek languages meant something was the absolute form of the word. Consider the phrase Holy, Holy, Holy (Isaiah 6:3), which essentially means “the holiest” in our language today.

12, which refers to God’s people on earth. The 12 tribes of Israel. The 12 disciples. The 144,000 people referred to in Revelation (12 x 12 x 1,000). The 12 gates of the new Jerusalem.

And 40, a number that corresponds with trials and periods of refinement. The 40 days and nights of the flood. 40 years in the wilderness after the Exodus. Jesus’ 40 days of fasting. 40 days of Lent. 40 days from Jesus’ resurrection to his ascension.

Does ascribing symbolic or theological meaning to these numbers mean that they didn’t “literally” occur in that manner? Not at all. But I do think understanding the deeper underlying pattern of these numbers enriches how we interpret these passages.

So What About 6 and 7?

7 is used more widely. The number of days of creation. The number of trips around Jericho before the walls fell. The Sabbath day. Sabbatical years (every 7th). The year of Jubilee (after 49 years or 7 x 7). The seven feasts of Israel. And the seven churches and angels referred to in Revelation.

It can be seen as a number of divine perfection or completion. It shows up consistently throughout the Bible and its symbolism is more widely understood.

But 6… is probably most known for the number 666, the mark of the beast from Revelation. But it also makes some other interesting appearances throughout the Bible.

Goliath’s height is six cubits and a span and had a spearhead weight of 600 shekels. Nebuchadnezzar’s statue is 60 cubits high and 6 cubits wide in Babylon. Even King Solomon is referred to as receiving 666 talents of gold yearly.

The number 6 feels like it has a mystery to it that rivals today’s “6 7”. Is it just coincidental that all of these references to 6 would just occur without some connective meaning? Is it possible that there was some deeper truth God was trying to convey to us? A common thread that ties all of these references together?

There are a range of interpretations on the meaning of 666 and the number 6 more broadly. One theory posited is that the number was meant to signify the Roman Emperor Nero. The Hebrew letters also had numerical values associated with them. Add those up for the name Nero Caesar in Hebrew and you get 666. It could have been a coded way of referring to the emperor while being subjected to oppression.

But another theory that I personally find more convincing allows us to see the significance of 6 more broadly than just ascribing it to one man or empire. One that draws out the consistent pattern for all those aforementioned references.

I think the key is found in the purpose of the sixth day of Creation, when man was created and our responsibilities were given. And maybe the best way to illustrate this is by considering a circle.

Remnants and Remainders

As we approach Pi Day (3/14) in a couple of months, which just so happens to be Tristan’s birthday too, math nerds celebrate this incredible phenomenon with circles. That the constant pi (π) used to calculate the circumference from a circle’s radius is constant and yet cannot be reduced to a definable fraction.

Most people in their childhood memorized the constant pi (π) to two decimal places – 3.14. Some strived to memorize many more decimal places than that. But no one can come close to memorizing the number of decimal places computers have calculated this value to.

By the end of last year computers had measured to 314 trillion decimal places. And yet, no repeating pattern has been found that would allow us to state a definitive number. Amazing!

For routine calculations we simplify this number, trimming off the extra decimal places to make it “close enough” for our purposes.

Funny enough the circumference of a circle is pretty close to 6 times the radius (2πr). The actual length however is 6 times the radius plus some remainder or remnant that we can’t calculate exactly and almost certainly never will.

Similarly, 6 in the Bible seems to correspond with man’s own dominion and that which we can control. It is calculable, predictable, rational, and replicable.

6 times the radius may get us close to the correct answer but we would still be discarding or ignoring the remnants and remainders needed to arrive at the actual answer.

This pattern extends beyond geometry too. Throughout many cultures and eras, man’s tendency to veer towards total control comes at the cost of those remnants and remainders that aren’t easily understood or are inconvenient.

Man’s dominion can turn into domination or totalitarianism. That was the error of Nero of Rome. The error of King Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon. The error of Goliath and the Amalekites. And even of King Solomon during the later chapters of his reign in Israel. We don’t have to think long to come up with modern versions of this exact impulse for control.

God called us to rule over the world and subdue it. But that was all to be done within the context of God’s ultimate rule over everything. The use of 6 in Biblical storytelling seems to emphasize the absence of Day 7, the day of God’s rest or, in other words, the day the God actually establishes his reign over his created cosmos.

666 (6 repeated three times) is the manifestation of the worst of man’s pride and the authoritarian actions that result. That is something we should all be on guard for in our hearts. The dismissal of the remnant and remainder. The exclusion of God, who can also be found in the margins, in the inexplicable, the irrational, and even the playful.

So whenever I hear “6 7” it reminds me to be intentional about leaving room for those things that can’t be measured or forced by our own efforts. Love, play, rest, and even relationships with inconvenient people because God has set an example in all of these.

And first and foremost making room for a god who calls us to lean not on our own strength and understanding, but on His. Even when it doesn’t completely make sense.

And maybe a similar humility spills over into how we parent.

“6 7”